Once upon a time making movies used to be free. Execs were flush with lucrative DVD/Blu-Ray deals and Television was generating a huge longtail of revenue. But as all good things must come to an end, so did rampant production of B-level action movies that stocked the clearance buckets at Wal-Mart. Here’s a step-by-step look at how it all used to work.

Step 1: Equity

Cash investments made by an investor, group of investors, and personal investments by friends & family. Equity investments that gives the investor a stake in the film and will be paid back (usually principal + 20%) before profit is seen by the filmmakers due to having the most risk.

Step 2: Pre-Sales

These are distribution agreements usually constructed at one of the major film markets (Cannes, Berlin, Toronto, American Film Market) before the film enters production. The distributor will determine the value of the project based on script, talent, marketing strategy, and this will in turn allow you to take out a bank loan using the distribution agreement as collateral. Pre-sales investments require that the producer pay back the bank its loaned capital before profiting on their respective upside.

Step 3: Gap

Now that you have part of the budget from the combination of private equity and distribution agreements, you can now get a loan from the bank or film financier based on the unsold territories of the film (and additional elements of collateral such as the intellectual property “IP” or corporate guarantees). Gap financing is only available when other elements have been put in place and there is sufficient assurances for the investor to “bridge” against.

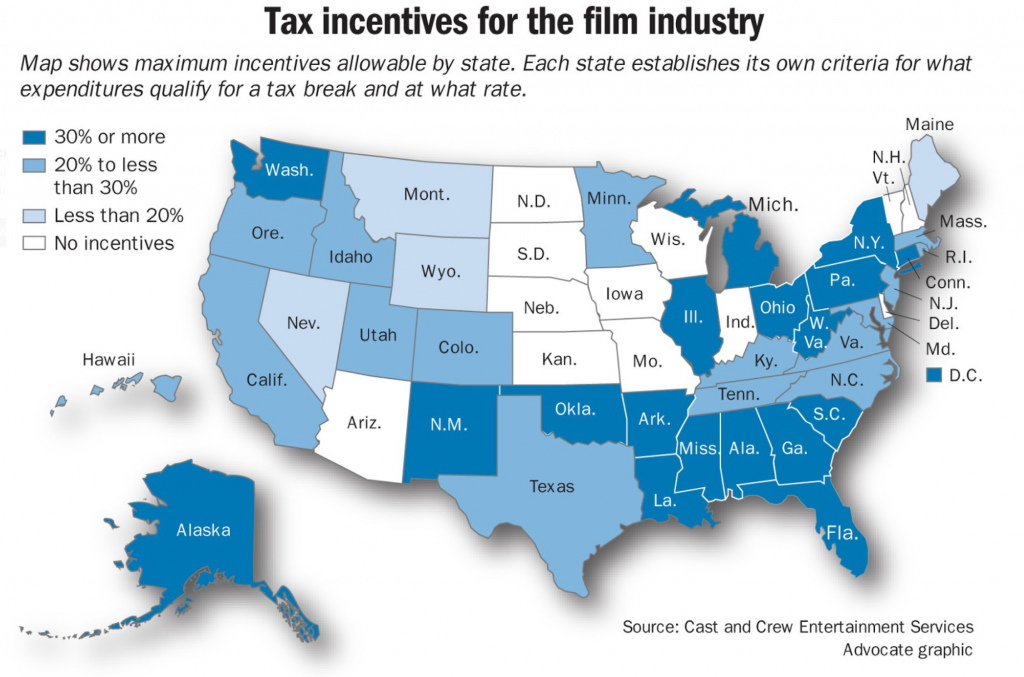

Step 4: Tax Incentives

Various states and countries have legislation in place to incentivize producers to film in those respective places in the form of tax credits. These production subsidies require that the producer hire a set number of local crew, rent from local suppliers and vendors, and run payroll through local financial institutions. Tax credits must be applied for and often require a lot of time (12–18 months) and paperwork. There are event some credits that are transferable or sell-able/trade-able such as in New Mexico, NOrth Carolina, Georgia, Michigan, and New York among others.

Step 5: Deferred & Crowdfunding

Another technique is to negotiate a deferred deal, which allows producers to avoid nearly all costs on a project by stating that crew, cast, locations, services, and vendors are all rendered up front at no cost until the film makes money. These types of financing structures are difficult because experiences cast and crew are usually unwilling to work without any assurances (bird in the hand is worth two in the bush). Meanwhile crowdfunding through Kickstarter or IndieGoGo allows capital to be raised on a donation basis without exchange of equity.

Step 6: Mezzanine Financing

Mezzanine financiers come in last in the finance pipeline and exit first. They are often the source of last minute financing in case a film goes over budget.

Great, so now that we’re all up to speed we can talk about the free movies. As late as 2014, films with budgets in the 8 figure range were able to completely finance through pre-sales alone. As an example, let’s take Fury which starred Brad Pitt, Shia LaBeouf, and Logan Lerman. The film’s budget was about $68 million. There was a tax credit for shooting in the UK of 25% but that would only include everything that happened there below-the-line so we’ll be conservative and say $40 million was eligible for tax credit, giving us a cool $10 million. In order to recoup the rest of the $58 million, pre-sales were made to territories across the world. A large deal worth $40 million was sold to Sony for domestic and some of the major international territories, and the rest of the world easily made up the remaining $18 million. So without any equity, we’re able to produce a film for zero risk. Having Sony on board with Brad Pitt starring is the primary reason this was at all possible (though casting a 50 year old staff sergeant would suggest he wasn’t quite good at his job) with the inclusion of David Ayer hot off the success of End of Watch.

Today this movie has about a half of the value internationally as it did just 4 years ago. As mentioned above, with the influx of local content starring homegrown talent, the need for a film like Fury isn’t as strong as it once was. While the film performed sufficiently for a total of $211 million, the ROI isn’t anything near what franchises, tentpoles, or sequels expect to earn globally today. Meaning, if these mid budget star vehicles with original screenplays can no longer be made for free, they most likely won’t be made at all.